The South Carolina Supreme Court reversed a lower court ruling Wednesday, stating that private organizations entrusted with millions in tax dollars to promote tourism are not subject to public information requests.

This Article was originally published by The City Paper. See original article by clicking here

The Supreme Court’s ruling comes after a years-long battle between the Hilton Head-Bluffton Chamber of Commerce and Skip Hoagland of DomainsNewMedia.com LLC. Beginning in 2012, Hoagland requested extensive financial documents from the chamber, questioning the organization’s expenditures of public tax dollars.

Under South Carolina state law, designated marketing organizations (DMO) such as the Hilton Head-Bluffton Chamber of Commerce receive millions of dollars in accommodations taxes from local municipalities. This money is to be used solely for promoting and marketing these communities as tourist destinations.

Hoagland and DomainsNewMedia won an initial ruling, with a judge declaring the chamber a public body subject to records requests under the Freedom of Information Act. That decision has now been successfully appealed by the Hilton Head-Bluffton chamber in a 4-1 ruling by the state Supreme Court.

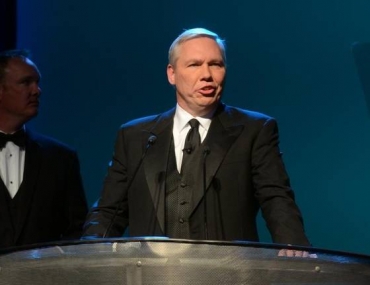

“The trial court held that the Chamber was a public body and, thus, was subject to FOIA’s provisions. We reverse,” wrote Justice John Kittredge, who was joined by Chief Justice Donald Beatty, and Justices Kaye Hearn and George James. “We hold, as a matter of discerning legislative intent, that the General Assembly did not intend the Chamber to be considered a public body for purposes of FOIA as a result of its receipt and expenditure of these specific funds.”

In their decision, the justices found that although the receipt of public funding does qualify a DMO as a public body under the Freedom of Information Act, that designation is superseded by the specific laws governing the allocation of accommodations tax dollars.

“Here, as noted, there is a specific statute (or proviso) that directs the local governments to select a DMO to manage the expenditure of certain tourism funds and requires the governments to maintain oversight and responsibility of the funds by approving the proposed budget and receiving an accounting from the DMO,” the justices write.

Undeterred by the Supreme Court’s decision, Hoagland said he would continue to pursue legal action, even if it meant looking to the FBI, IRS, and Department of Justice to pursue forensic audits and investigations into the expenditures of DMOs. In the meantime, Hoagland also plans to call on fellow citizens to lean on their local mayors and city council members to push for more transparency in how accommodations tax money is spent.

“This is just beginning. There is the old saying, ‘There’s more than one way to skin a cat.’ I’m going to find another way to skin the cat,” says Hoagland, who vowed to only increase his incredibly vocal criticism.

Of course, Hoagland’s fight against DMOs extends beyond just the Hilton Head-Bluffton Chamber of Commerce. Among the DMOs across South Carolina that have drawn the retired businessman’s attention is the Charleston Area Convention and Visitors Bureau (CACVB). Similar to the case with the Hilton Head chamber, Hoagland has threatened legal action against CACVB regarding a partially unfulfilled request for the private nonprofit’s financial records. Hoagland’s contention with the CACVB was profiled in a recent City Paper cover story, in which an attorney for the group said that the CVB’s exact expenses should not be subject to FOIA requests as revealing such information would provide an unfair advantage to competing designated marketing organizations.

As it relates to the level of oversight offered by local governments when it comes to DMOs, the City Paper‘s recent cover story pointed out that the CACVB does not provide the City of Charleston with an annual budget or quarterly spending reports, according to city Chief Financial Officer Amy Wharton. Instead, the CACVB offers an annual audit which provides a brief overview of its revenue and overall expense total. The CACVB receives accommodations funding from multiple local municipalities, all of which are represented by a member on the nonprofit’s board of governors, which is tasked with approving the organization’s annual budget.

Justice John Few was the lone voice of dissent in the state Supreme Court’s decision. Pointing back at a potential lack of transparency and oversight he observed during court arguments, Few wrote, “To the extent the policy behind the FOIA could be furthered by ‘oversight’ from public officials, the record in this case reveals the information provided to those public officials does not allow the officials to determine how the funds are being spent.”

Few then recounts asking an attorney for the Hilton Head-Bluffton chamber about a specific line item listing a $200,000 expenditure for search engine marketing in the chamber’s proposed 2013-14 budget.

“After several other questions and answers, counsel agreed with the following assertion: Unless somehow the town takes the initiative to learn from the Chamber what the $200,000 represents, then in our scenario, a member of the public would never be able to gain access to the individual vendors, whether they submitted bids, what were the bids, what was the highest bid, and on and on and on.”

Last year, attorney Jay Bender, on behalf of the South Carolina Press Association, filed a legal brief in the Hilton Head-Bluffton chamber’s appeal case. Bender and the Press Association, of which the City Paper is a member, argued that as the recipient of public funds, the chamber was subject to the full reaches of the Freedom of Information Act. Bender voiced his disappointment in the Supreme Court majority’s decision, saying that if the court’s analysis is correct, then the General Assembly intended for millions of dollars of public funds to go to private organizations without public oversight, therefore affirming a “scheme with great potential for money laundering.”

“I think the dissenting opinion points out quite correctly that the people shut out of the monitoring process with respect to public funds are the very people from whom the money comes,” says Bender “The public is foreclosed from having any meaningful oversight into how accommodations tax money is spent.”

With the Supreme Court majority ruling that the public should not have the opportunity to review any details related to accommodations tax expenditures, reserving oversight for elected officials, Bender fears that the decision will only fuel speculation that public money may be used to fund political supporters of chambers and other DMOs. While the state’s Supreme Court feels confident that the necessary oversight to prevent such activities is already in place, not everyone is so sure.

“It’s an invitation for the fox to guard the hen house,” says Bender, “and for public money to end up in the pockets of public officials.”